Listen to my narration of this essay:

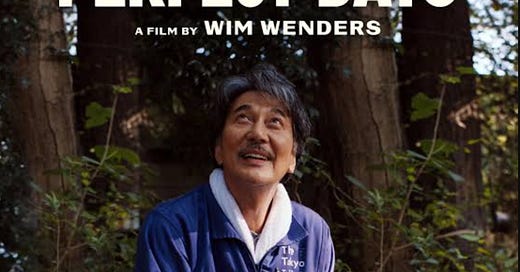

Komorebi (木漏れ日) means "sunlight filtering through the trees." In Wim Wenders’ film Perfect Days, the main character, an older single man named Hirayama, leads a simple life as a worker for Tokyo Toilet. Throughout each day, he notices the komorebi from his window, at the toilets he cleans, and in the park where he eats his convenience store sandwich. This quiet but recurring detail is a clue to what gives him his ikigai (生きがい)—his reason for being.

I love the film because Hirayama’s quiet, intentional lifestyle mirrors aspects of my own experiences in Japan—both past and recent. I’ve lived in Tokyo several times. Watching it brought back memories of tradition, change, solitude, and deep emotional connection. I’d like to share a few reflections from my own life that Perfect Days sparked.

Reconnecting with Tokyo, Then and Now

While the world was still emerging from the isolation of Covid, my son Joe invited me to visit Tokyo, where he was studying as a graduate student. For this visit, I decided to rent a small, traditional house in Asakusa, an old neighborhood known for its temples, narrow alleyways, and the Sumida River—so often seen in woodblock prints. From my balcony, I could see the glowing Skytree tower. I stayed in that little house for a whole month so I could get to know the neighborhood. When I saw Perfect Days, I was delighted to see that familiar glowing tower in so many scenes.

Living in Asakusa in my sixties was a very different experience from earlier visits to Tokyo. Decades ago, I lived near Shibuya, the trendy, newer part of Tokyo where the unique Tokyo Toilet buildings exist. I was still married, with Joe just a toddler. I can relate to the harried young mother Hirayama encounters when he finds a crying child. Back then, Asakusa was a place I only went to buy traditional arts and crafts, not a place I called home. I was too busy then to notice the Komorebi. Watching Hirayama go about his life in these different Tokyo neighborhoods made me reflect on how different I was when I lived in those places.

A Familiar Home, A Changed Self

Hirayama’s modest home immediately reminded me of the house I rented in Asakusa a few years ago. It was a typical older Japanese house—tatami mat room upstairs accessed by a steep staircase, with a small kitchen, bath, and living area below. That layout echoed the homes I knew well: my grandparents’ house in Gokokuji and my host family’s house from my Study Abroad year. The grassy scent of tatami, the light fixtures, and the tight, compartmentalized rooms awakened old memories. I remembered how, in the ’70s and ’80s, my Japanese friends used to joke that their homes were “rabbit hutches”—so different from sprawling American homes with four or five bedrooms and huge kitchens.

But modesty in housing has deep cultural roots. Historically, even upper-class samurai were expected to live simply. In a land of earthquakes, typhoons, and tsunamis, homes were not built to impress since they were likely to be destroyed. Wooden structures could be easily rebuilt. Even tea houses were designed with low entrances to ensure everyone—regardless of rank—had to bow to enter. A home in Japan is a quiet but temporary retreat from the world. Newer structures, like the Tokyo Toilets, are more sturdy but they still reflect simplicity and practicality.

Ritual and Reverence in the Everyday

In fact, the film presents Hirayama’s daily routine almost like a tea ceremony: methodical, deliberate, and full of awareness. His morning ritual—trimming his mustache, buying a canned coffee, playing a cassette tape—is as choreographed as the tea lessons I once took as a student. Cleaning toilets is his job, but he does it with care and quiet reverence. These public toilets, part of the Tokyo Toilet Project, are beautiful works of design—just as every scene of the film that Wenders made. Hirayama doesn’t speak much, but his actions show love and pride in each task. But as visitors to Japan know, even ordinary modern toilets are marvelous machines to be appreciated and enjoyed.

This deep respect for cleanliness and order runs through Japanese culture. I remember how, even in middle school (chuugakkō), we cleaned our own classrooms and bathrooms. Later, as an English teacher at a Japanese engineering firm, I was also expected to help with chores like cleaning and snow shoveling. I was so impressed by the garbage trucks. They were spotless, the workers’ uniforms crisp. To care for a space is not a lowly task—it is an honorable one.

Connection Through Solitude

Though Hirayama lives alone, he is not isolated. He interacts warmly with a cast of imperfect people—his carefree co-worker, a troubled niece, the bartender he quietly falls for, and a homeless man whom he treats with dignity. His relationships are quiet but deeply felt. Like the film Groundhog Day, Perfect Days uses repetition to reveal a person’s character through his small daily acts.

Hirayama channels his enthusiasm for life through his photographs of komorebi, his collection of 70’s and 80’s music cassette tapes, and reading every night—everything from Aya Koda’s Tree to Faulkner and Highsmith. Even his dreams, shaped by these stories, ripple with energy and hidden emotion. His simple life is not empty—it’s emotionally rich, full of quiet joys, humor and deep sorrow.

Food, Baths, and the Kindness of Strangers

One of my own greatest joys of living in Tokyo was eating out. Like Hirayama, I’d find comfort in regular stall food, a tiny neighborhood eatery or a delicious treat from the convenience store. The same underground passage he walks in Asakusa is one I used to pass through daily. There, customers are welcomed like family, given an ice cold lemon shochu and warm words: “Otsukaresama!”—well done for another hard day of work.

At day’s end, Hirayama visits the sentō, the public bath. I also shared this ritual, soaking in hot water with neighbors—many elderly, all stripped of pretense. Whenever I got together with Joe, going to the sentō was part of our day. I could hear the men on the other side of the dividing wall also enjoying their bath. It was a daily cleansing not just of body but of spirit. No matter what was going on in the world, I felt better after a long hot soak at the public bath.

Conclusion: Meaning in the Moment

Perfect Days is a quiet masterpiece, a meditation on purpose and awareness. Through Hirayama, we’re reminded that a meaningful life need not be grand or loud. It can be lived in routines, in silence, in cleaning a toilet, sharing a bath, or having a drink with strangers. The Japanese response to Covid—unified, kind, respectful—reflects this same ethic of collective care.

I miss that about Tokyo, especially during these troubled times. Why do I feel so anxious in this country, while I felt so safe in Tokyo?

Like komorebi, Hirayama’s daily experiences are fleeting and beautiful. In watching Perfect Days, I saw myself—not just who I was when I lived in Tokyo, but who I’ve become. I remind myself to pay attention every day. The light that filters through the trees isn’t dramatic, but it leaves a lasting impression.

I enjoyed your review of the movie which I also enjoyed. The roles of repeated ritual is so foreign to our Americanized lives. We can hardly bear to do something again because we’re distracted by the next bright thing!